In 1903, the Germanic Museum was dedicated at Harvard University. It was the brainchild of Kuno Francke (1855-1930). There are probably few people today who are aware that such a museum was ever created, or who its creator was. But when it opened, it made international news. Its history reflects the ups and downs of German-American relations in the 20th century.

Kuno Francke

Kuno Francke was a professor of the History of German Culture at Harvard who taught German literature from a cultural historical perspective. He wrote that he explored German literature “from the point of view of the student of civilization rather than from a linguistic or the literary scholar.” He said that his research led him “to see literature primarily the working of popular forces to consider it chiefly as an expression of national culture.”

Students flocked to his courses and his publications were widely read after he came to Harvard in 1884. In time, he emerged as one of the foremost representatives of German-American cultural exchange. In 1897, he and two of his colleagues published a proposal on The Need of a German Museum at Harvard.

He felt that this was absolutely necessary to transmit an understanding of German culture, noting “it is a principle now generally accepted that a nation’s history cannot be studied adequately without a consideration of its achievements in the monumental and domestic arts. Nowhere does the spirit of a people manifest itself more clearly and impressively than in the buildings devoted to public worship or public deliberations, in the images embodying the popular conception of sacred legend or national tradition, in the appliances for private comfort and security.”

The proposal also stated that there were already a variety of museums in the U.S.: “But nowhere in this country is there a chance of studying consecutively even the most important monuments of Germanic civilization. Nowhere in this country can the student obtain a vivid impression of the life and customs of our forefathers, from the early Teutonic times to the later Middle Ages, such as is afforded by the Germanic Museum at Nuremberg and other European locations. Nowhere can be given an accurate conception of the wonderful Romanesque cathedrals of the twelfth century, of the extraordinary power of German sculpture in the thirteenth, of the exquisite works of German woodcarving in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries – or even of the work of such great men as Peter Vischer and Dürer.”

The proposal met with international support and interest. In 1902, Prince Heinrich of Prussia visited the U.S. and during his visit at Cambridge, where he received an honorary degree, he made the spectacular announcement that his brother, Kaiser Wilhelm II, would make “a magnificent gift to the Germanic Museum, which will include key monuments in the development of German sculpture.” Given this kind of backing, the Museum was assured of success and was officially dedicated the following year.

In 1906, the Emperor William Fund was established in honor of the silver wedding anniversary of the Kaiser. It consisted of $30,000 from the American Friends of the Germanic Museum and Adolphus Busch, the well-known German-American beer baron of St. Louis, who served as president of the Germanic Museum Association. And four years later, Busch donated an additional $265,000 for the construction of a home for the museum – the Adolphus Busch Hall at Harvard. More support came from St. Louis: in 1913, Busch’s son-in-law, Hugo Reisinger, gave $50,000 to the museum.

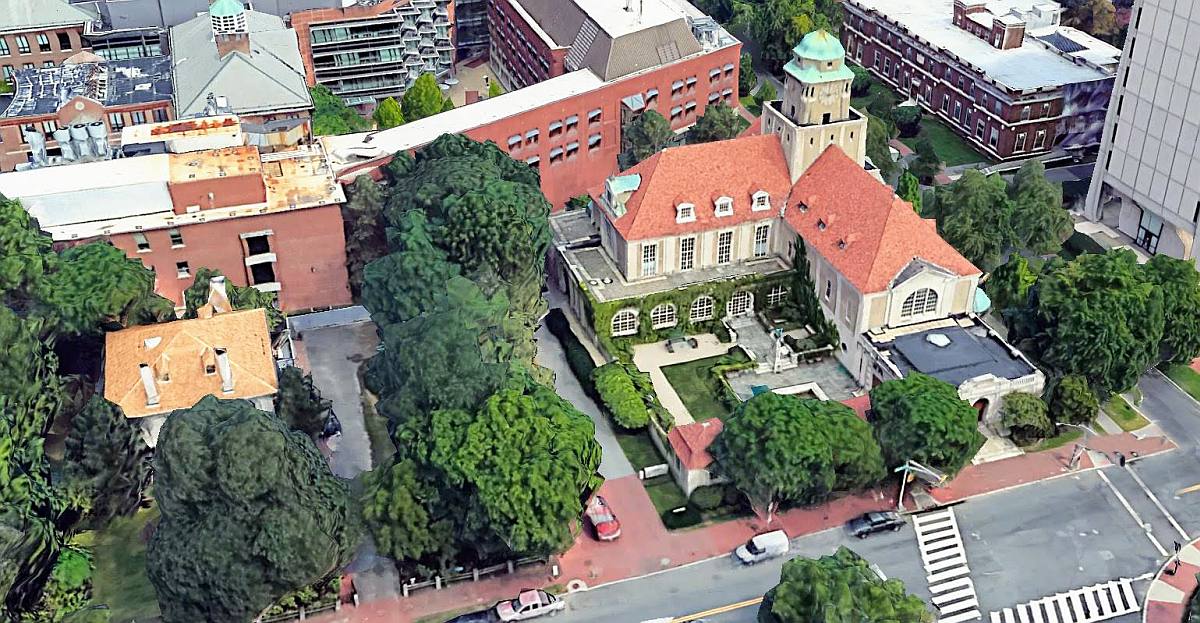

The Adolphus Busch Hall is without doubt one of the most impressive and beautiful buildings on the Harvard campus. Francke filled the museum with reproductions of original works of German sculpture and architecture, using them to illustrate and teach the history of German civilization and culture. At the same time, Francke actively promoted German-American exchange programs to enhance cross-cultural relations between the U.S. and Germany.

Adolphus Busch Hall

In 1905, he established an academic exchange program that made it possible for professors from Germany and America to teach and do research on both sides of the Atlantic. Francke also edited a landmark work, the multi-volume German Classics of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Masterpieces of German Literature (1913-14). Here one finds translations not only of the great works of German literature, but from various areas of German cultural life, especially philosophy.

And then came World War I. Francke did his best to promote peace based on the cultural relationships he had worked so hard for. After the U.S. declaration of war against Germany in 1917, the Germanic Museum was closed and Francke retired. But the museum reopened in 1921 with the dedication of the new Adolphus Busch Hall, which bears the inscription: “Es ist der Geist, der sich den Körper baut” (It is the spirit that builds itself the body).

In 1925, Francke published an illustrated guide, Handbook of the Germanic Museum, and in 1927 a collection of essays, German After-War Problems. Here he wrote that he considered it to be “the paramount duties of German-Americans, as heirs and guardians of German culture in this country” to cultivate “these precious legacies of our Old World ancestry.”

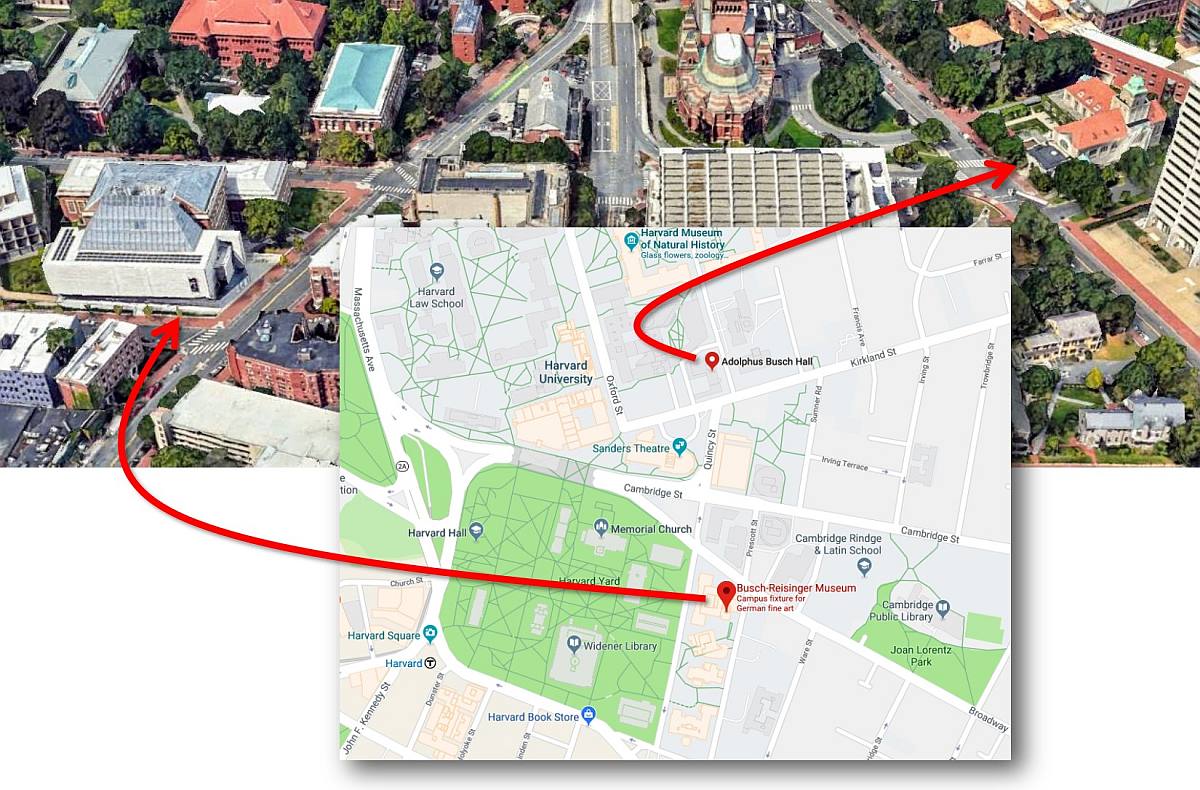

During World War II, the museum was also unfortunately closed due to the spirit of the time. After the war, the daughter of Adolphus Busch, who was the widow of Hugo Reisinger, gave $205,000 to re-open the museum. And in 1950, its name was changed to the Busch-Reisinger Museum of Germanic Culture, but it is now simply known as the Busch-Reisinger Museum. In 2014, the museum moved to its new location (see map below), see FAQ page for more information about visiting Adolphus Busch Hall.

Today the museum focuses more on modern, rather than historical periods of German art, indicating a more contemporary focus than that of its creator, who sought an understanding of German culture by concentrating on the historical foundations of German art and architecture. In spite of the name change and the more contemporary focus, the museum continues on as the major museum of its kind in the U.S. It survived the hard times of the past century and stands as a symbol of the strength of U.S.-German relations, as well as to the support it has received from friends in both countries, especially from the Busch family of St. Louis.

A visit to Harvard’s campus in Cambridge would be incomplete for anyone interested in German culture, if it did not include a stop at the Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum. One should also take time to visit the majestic Adolphus Busch Hall, the previous home of the museum. And later on, take time to read some of the works of its creator, Kuno Francke.

Location Map

Links

German Ideals of Today: And other Essays on German Culture, by Kuno Francke

The German Spirit, by Kuno Francke

Handbook of the Germanic Museum, by Kuno Francke

For further information on Francke and the Germanic Museum, see:

German-Americana: Selected Essays, by Don Heinrich Tolzmann

About the Author

Dr. Don Heinrich Tolzmann

is a member of the Advisory Board and Historian of GAMHOF,

Book Review Editor of German Life

and Associate Publisher of Germerica.net