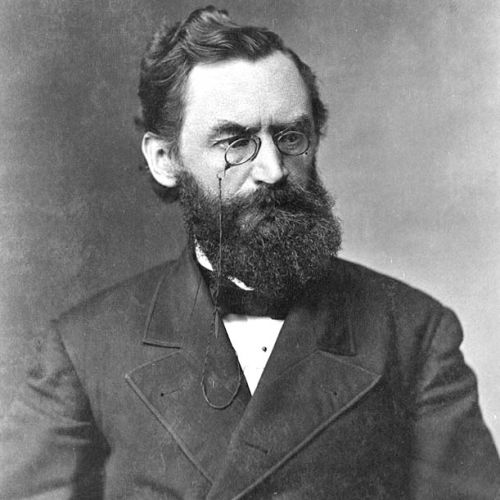

Carl Christian Schurz was a German revolutionary, American statesman and reformer, and Union Army General in the American Civil War. He was also an accomplished journalist, newspaper editor and orator, who in 1869 became the first German-born American elected to the United States Senate.

His wife, Margarethe Schurz, was instrumental in establishing the kindergarten system in the United States. During his later years, Schurz was perhaps the most prominent independent in American politics, noted for his high principles, his avoidance of political partisanship, and his moral conscience.

He is famous for saying: “My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right.” Many streets, schools, and parks are named in honor of him, including New York City’s Carl Schurz Park.

Schurz was born in Liblar (now part of Erftstadt), Germany on March 2, 1829, the son of a schoolteacher. He studied at the Jesuit Gymnasium of Cologne, and learned piano under private instructors. Financial problems in his family obligated him to leave school a year early, without graduating, to help manage his family’s financial affairs. Later he graduated from the gymnasium by passing a special examination, and he entered the University of Bonn.

In 1855, Schurz settled in Watertown, Wisconsin, where he immediately became immersed in the anti-slavery movement and in politics, joining the Republican Party. In 1857, he was an unsuccessful Republican candidate for lieutenant-governor. In the Illinois campaign of the next year between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, he took part as a speaker on behalf of Lincoln – mostly in German -which raised Lincoln’s popularity among German-American voters (though it should be remembered that Senators were not directly elected in 1858, the election being decided by the Illinois General Assembly). Later, in 1858, he was admitted to the Wisconsin bar and began to practice law in Milwaukee. In the state campaign of 1859, he made a speech attacking the Fugitive Slave Law, arguing for states’ rights. In Faneuil Hall, Boston, on April 18, 1859, he delivered an oration on “True Americanism,” which, coming from an alien, was intended to clear the Republican party of the charge of “nativism”. Wisconsin Germans unsuccessfully urged his nomination for governor in 1859.

In spite of Seward’s objection, grounded on Schurz’s European record as a revolutionary, Lincoln sent him in 1861 as ambassador to Spain. He succeeded in quietly dissuading Spain from supporting the South. Persuading Lincoln to grant him a commission in the Union army, Schurz was commissioned brigadier general of Union volunteers in April, and in June took command of a division, first under John C. Frémont, and then in Franz Sigel’s corps, with which he took part in the Second Battle of Bull Run. He was promoted major general of volunteers on March 14 and was a division commander in the XI Corps at the Battle of Chancellorsville, under General Oliver O. Howard, with whom he later had a bitter controversy over the strategy employed at that battle, resulting in their defeat by Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. He was at Gettysburg (a victory for the Union) commanding the Third Division of Howard’s XI Corps, and at Chattanooga (also a victory for the Union side), at which he served with the future Senator Joseph B. Foraker, John Patterson Rea, and Luther Morris Buchwalter.

In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent Schurz through the South to study conditions; they then quarrelled because Schurz approved General H.W. Slocum’s order forbidding the organization of militia in Mississippi. Schurz’s report, suggesting the readmission of the states with complete rights and the investigation of the need of further legislation by a Congressional committee, was ignored by the President. In 1866, Schurz moved to Detroit, where he was chief editor of the Detroit Post. The following year, he moved to St. Louis, becoming editor and joint proprietor with Emil Praetorius of the Westliche Post (Western Post), where he hired Joseph Pulitzer as a cub reporter. In the winter of 1867-1868, he traveled in Germany – the account of his interview with Otto von Bismarck is one of the most interesting chapters of his Reminiscences. He spoke against “repudiation” (of war debts) and for “honest money” (the gold standard) during the Presidential campaign of 1868.

In 1869, he was elected to the United States Senate from Missouri, becoming the first German American in that body. He earned a reputation for his speeches, which advocated fiscal responsibility, anti-imperialism, and integrity in government. During this period, he broke with the Grant administration, starting the Liberal Republican movement in Missouri, which in 1870 elected B. Gratz Brown governor.

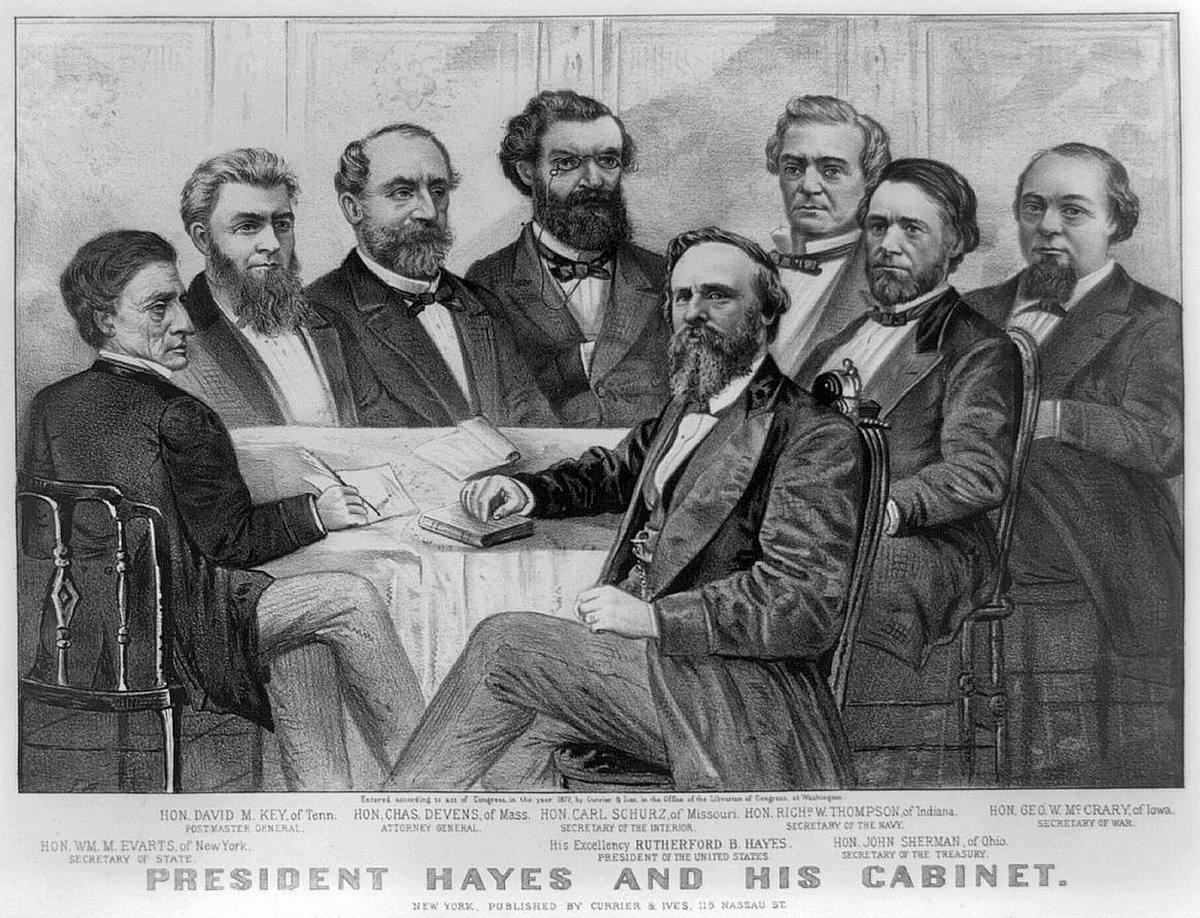

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him Secretary of the Interior, following much of his advice in other cabinet appointments and in his inaugural address. In this department, Schurz put in force his theories in regard to merit in the Civil Service, permitting no removals except for cause, and requiring competitive examinations for candidates for clerkships. His efforts to remove political patronage met with limited success. As an early conservationist, he prosecuted land thieves and attracted public attention to the necessity of forest preservation.

During Schurz’s tenure as Secretary of the Interior, there was a movement, strongly supported by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the War Department. Restoration of the Indian Office to the War Department, which was anxious to regain control in order to continue its “pacification” program, was opposed by Schurz, and ultimately the Indian Office remained in the Interior Department.

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to New York City. That year Henry Villard acquired the New York Evening Post and The Nation and turned the management over to Schurz, Horace White and Edwin L. Godkin. Schurz left the Post in the autumn of 1883 because of differences over editorial policies regarding corporations and their employees.] In 1884, he was a leader in the Independent (or Mugwump) movement against the nomination of James Blaine for president and for the election of Grover Cleveland. From 1888 to 1892, he was general American representative of the Hamburg American Steamship Company. In 1892, he succeeded George William Curtis as president of the National Civil Service Reform League and held this office until 1901. Carl Schurz lived in a summer cottage in Northwest Bay on Lake George, New York which was built by his good friend Abraham Jacobi. Schurz died in New York City and is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Sleepy Hollow, New York.